Sultans of the Opera

Turquerien und Alla Turca

1389 Battle of Kosovo was the first time the Ottoman army and the European nations of the time met in a military confrontation. This is the beginning of numerous warlike encounters between Orient and Occident in the centuries to come. The Ottoman dreams of expansion towards the West with the multiple siege of Vienna ended abruptly after the last siege of Vienna in 1683, where the Ottomans were repulsed by the Holy Alliance of Europeans.

However, the Crusaders had already fought against the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century and lost Jerusalem to them. All subsequent crusades were remembered by the European peoples through wars against Turks. As a result, the image of Turks was dominated by stereotypes that emphasized cruelty because of the Turkish wars.

The reception of the conquest of Otranto is an example of this expression of Turkish fear. But after Venice, in particular, wanted to create a more positive relationship with its eastern competitor after the first great war against the Ottomans and sent artists to the Sultan, the image of Turks in art changed lastingly.

Unrealistische Stereotypen wurden ersetzt, allerdings zunächst nur durch neutralere, realistische, da man immer auf die gleichen Bilder zurückgriff. Ein rein positives Bild eröffnete sich auch dadurch nicht. Der kriegerische Aspekt der Osmanen scheint im Vordergrund geblieben zu sein. Gleichzeitig nahm man aber gerade auch noch unter anderen Aspekten wahr und zeigte einiges Interesse an dem Anderssein. Oft genug konnte der „Türke“ geradezu zum Vorbild für alte und neue Tugenden werden. Türkische Motive fanden bereits im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert Eingang nach Europa. Das entsprach der Neugierde der Zeit für die exotische Kultur, die ja bis ins 19. Jahrhundert hinein unmittelbarer Nachbar europäischer Großmächte war.Im 16. Jahrhundert hatte sich zwischen Frankreich und dem Osmanischen Reich eine politische Freundschaft entwickelt. François I. war der schärfste Widersacher Kaiser Karls V. um die Vormachtstellung in Europa. Im ersten Krieg gegen Karl geriet François in Karls Gefangenschaft. Süleyman der Prächtige hatte den französischen König François I. aus der Gefangenschaft Karl des V. freibekommen. So hatte François eine Gesandtschaft an die Hohe Pforte in Konstantinopel geschickt aber der Gegenbesuch ließ mehr als 150 Jahre auf sich warten. Der Gesandte Süleyman Aga wurde von Ludwig in Versailles empfangen, wobei das Treffen in einem diplomatischen Eklat endete.

When Süleyman Aga was asked afterwards what impression the French king had made on him, he replied that “his master’s horse was much richer decorated when he went to the Friday prayer”. He made the king’s exaggerated order ridiculous in public. Ludwig commissioned Molière to write a piece which was to depict the Turks in a ridiculous manner, Lully composed the ballet comedy Le Bougeois gentilhomme especially at the request of Ludwig the 14th, to which Ludwig danced in oriental robes. And indeed, the “cérémonie turque” and the “Ballet des Nations” are the first receptions of Turkish music in opera literature.

Turkish fashion reached its peak in the 18th century: Ottoman legations arrived in Paris, Vienna and Berlin. Their magnificent receptions nourished the ideas of a lavishly rich fairyland.

Turkish fashion is no longer a means of dealing with collective fears in the style it was at the time of the bloody conflicts with the Ottoman Empire. More and more, La Turquerie is becoming the fashion of the time and, in addition to providing an occasion to dress up at courtly festivities, is also a welcome opportunity to retreat into the private sphere.

The courts built their own Janissary bands, made music in Turkish style and with Turkish motifs – and dressed up in Turkish style. August the Strong celebrated in Dresden the marriage of his son in 1719 in Turkish style. A Turkish wedding with opera performances, ballets and hunting parties. All of Europe was here. The crème de la crème of music, like the singer Senesino and the prima donna Faustina, sang to the music of composers such as Hasse, Lotti, Weiß, Heinichen and Quanz, who composed new music for this spectacle. The great masters such as Porpora and Handel were also present.

In honour of Maria Josepha August even staged a whole “Turkish Festival”. For this he not only had another Turkish palace prepared, but also converted entire infantry battalions into Janissary Guards. The Saxon recruits had to leave a “moustache à la Turque” and were armed with Turkish daggers and shotguns. Apparently the Ottoman fever knew hardly any borders, so August is said to have disguised himself as a sultan – in admiration for the omnipotence and military power of the ruler of the Bosporus, suspected from a European point of view.

Many a sabre may have been swung by the false Saxon Janissaries at the princely wedding in 1719. Among the absolute highlights of the Türcken Cammer in Dresden, however, are two Ottoman state tents. Under their richly embroidered fabric panels, visitors walk like August the Strong once did. His forefathers had already collected weapons and helmets, saddles and breastplates from the Orient, but it was only under his reign that Turkish fashion reached its absolute peak. While before the 18th century many pieces of the chamber arrived in Dresden as booty from the Turkish wars or diplomatic gifts, August 1713 sent his faithful valet Johann Georg Spiegel to Constantinople with a shopping list. These costumes, weapons and oriental utensils were also used in the numerous Turkish operas.

In addition to robes, weapons, carpets and tents, the costume also contained the desire for living exotic personnel such as slaves and eunuchs. Ten years earlier, for example, the gallant August had already had a liaison with a Turkish partner named Fatima.

Fatima gave him two children and was later married to Diener Spiegel. Meanwhile, the princely womanizer continued to work on the Saxon version of a seraglio: with his countless mistresses and lovers, he also saw himself in the tradition of eastern harem lords.

Music

The influence of the Turkish Ottoman on Western music consists above all in the adoption of percussion instruments (triangle, bell tree, cymbal, large drum), which in the Ottoman army should have a thoroughly deterrent function on the opponent. This military warlike “noise” then went into Western compositions as music “alle turca”.

Johann Adolf Hasse wrote his opera “Solimano II” in 1753, Paul-César Gibert’s “Soliman second ou Les Trois Sultanes” follows in 1761, David Perez’s opera “Solimano” is premiered in Lisbon in 1768 and Guiseppe Sartis’s “Soliman den anderen” in Copenhagen in 1770.

In 1782 Mozart finally staged his Singspiel “Die Entführung aus dem Serail”. The setting is a country house in Turkey, the main characters being three Europeans imprisoned as slaves and a fourth approaching their liberation, the owner of the country house, Bassa Selim, and his servant Osmin, who is also master of the European slave Blonde.

In his piece, Mozart takes up the common Turkish clichés of his century: Osmin is the foolish, bloodthirsty and exaggeratedly bramar-based Turk, who by his pompous words alone (“First decapitated, then captured, then speared on long sticks”) challenges people to outwit him. Yet he does not succumb to the cunning of the Europeans, but must give way to the wisdom of his Lord, who is not called Selim (= Solomon) for nothing. Both represent the defence mechanisms of Europe against the superior enemy of earlier times: Neither was a stupid, clumsy Turk really an enemy, nor one whose wisdom one wanted to acknowledge unreservedly (“He who can forget so much grace is viewed with contempt”).

Joseph Martin Kraus followed in Stockholm in 1789 with “Soliman II eller De tre sultaninnora” and Franz Xaver Süssmayr in Vienna in 1799 with his opera “Soliman der Zweite oder Die drei Sultaninnen”. Both are based on the story “Soliman II” from the “Contes moraux” by Jean-Francois Marmontel (1761).

Project description

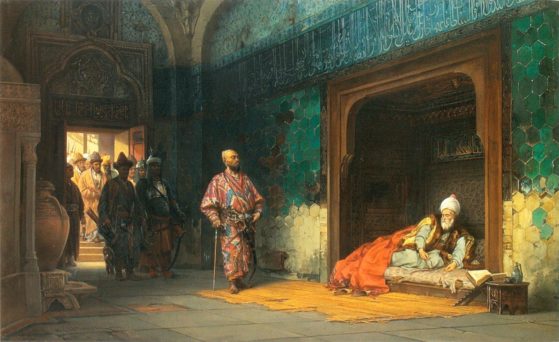

The Alla Turca opera is a genre that is indispensable in late Baroque and classical music-making. But the European version of life at the sultan's court always oscillates between the depiction of power-hungry, bloodthirsty rulers and the sultry, erotic atmosphere of the harem. So it is not only time to redefine the genre, but to show the world of the seraglio as it really was. In various opera scenes conceived according to the principle of baroque pastiche, the Pera Ensemble takes the audience on a fascinating journey into new (sound) worlds full of passion, devotion, love and the quest for power. The musical realisation is off the beaten track of Turkomania and exoticisms. Through the congenial combination of western baroque music and classical Turkish art music, the concept of aesthetic shock familiar from the 18th century is reworked here for a cosmopolitan audience of today.

All diese Opern mit türkischen Motiven, Geschichten und Turquerien haben oft einen Sultan als Vorbild oder Held.

Wir möchten die Highlights aus diesen Opern zu einem neuen Programm und Konzerterlebnis gestalten. Halbszenische Bearbeitung von o.g. Werken.

Solisten werden extra angefertigte Kostüme im Serailstil tragen.

As we have seen, the confrontation with the “other” has been a topic since the Middle Ages. However, in the 21st century this is more topical than ever with 3.5 million migrants of Turkish origin in Germany, many war refugees flowing towards Europe, clash of cultures, Islamist terror and Islamophobia. The enthusiasm in Europe for the Turks and Alla Turca can serve as a historical example to build a bridge to the present. Instead of pointing out with the index finger to meet the foreigner with respect at eye level, music can be much more effective and sustainable as a universal language. Especially when great thinkers such as Goethe and composers such as Mozart have taken an interest in Islamic and Turkish culture.

Musik als Bindeglied zwischen den Jahrhunderten und den Kulturen.

Purpose

As we have seen, the confrontation with the “other” has been a topic since the Middle Ages. However, in the 21st century this is more topical than ever with 3.5 million migrants of Turkish origin in Germany, many war refugees flowing towards Europe, clash of cultures, Islamist terror and Islamophobia. The enthusiasm in Europe for the Turks and Alla Turca can serve as a historical example to build a bridge to the present. Instead of pointing out with the index finger to meet the foreigner with respect at eye level, music can be much more effective and sustainable as a universal language. Especially when great thinkers such as Goethe and composers such as Mozart have taken an interest in Islamic and Turkish culture.

Music

as a bridge between centuries

and cultures.